The Book Group Reading of ‘Fascism: A Warning’ by Madeleine Albright with Bill Woodward

Deep State Book Club

December’s choice of book is by a woman who has spent nearly four decades as a major force in American politics and international affairs, as such her newest book ‘Fascism: A Warning’ was bound to cause people to sit up and take notice. Indeed, over half of those who voted in the poll to choose our December read voted for this book.

Madeleine Albright tells us what she intends with the book right from the cover, the book is a warning, a wakeup call, it asks us to be aware that ‘strong men’ are on the rise and that the current American President openly celebrates them. But is what she describes in her book Fascism and how good a job does she do in setting out her fears and concerns? Perhaps more importantly, what is her prescription for dealing with those concerns?

Albright in conversation with Andrew Rawnsley of the Guardian does not believe Fascism to be an ideology but “I think it is a method, it’s a system.”

A Fascist, Albright believes:

“Is someone who identifies strongly with and claims to speak for a whole nation or group, is unconcerned with the rights of others and is willing to use whatever means are necessary – including violence- to achieve his or her goals.”

This definition is extremely broad, it would bring within its remit many forms of political and terrorist identity, not all of them fascist. This emphasis on the broad mechanics of Fascism is unhelpful in defining exactly what the reader needs to be warned about. Albright states she does not want to be pinned down to ‘labels’ preferring to concentrate on actions but it is this lack of clarity which leads to criticism of the book, for if you can not define Fascism with clarity how are you to recognise it and, more importantly, recognise the social, economic and political conditions that give rise to Fascism and make it attractive.

Robert Paxton in his 2004 book ‘The Anatomy of Fascism’ defines it Fascism as:

“A form of political behaviour marked by obsessive preoccupation with community decline, humiliation or victimhood and by compensatory cults of unity, energy and purity, in which a mass-based party of committed nationalist militants, working in uneasy but effective collaboration with traditional elites, abandons democratic liberties and pursues with redemptive violence and without ethical or legal restraints goals of internal cleansing and external expansion.”

Albright does touch on these themes as we progress through the book. Early chapters dealing with historical Fascists (Hitler, Mussolini and Franco) together with later chapters on Stalin, Hugo Chavez, Recep Erdogan, Vladimir Putin, Kim Jong-il and the Bosnian conflict are all grounded in the authors experiences as a child refugee and later as a diplomat having to sit across the table from these men. Albright herself concedes that in relation to the latter group, with the exception of Kim Jung-un, the current crop of authoritarian leaders may share the traits of Albright’s definition of fascism but they are not Fascists.

Another problem with Albright’s concentration on method rather than a more precise definition that would allow us to identify more accurately that of which she warns, is that it is not method alone that saw Hitler and Mussolini elevated to power. Mussolini won 4,796 votes out of 315,165 in 1919, to be then appointed Prime Minister in 1922. Hitler’s Nazi Party placed ninth in 1928 soared to first in elections in 1932. Societal ills and, what Robert Paxton calls, “conservative complicities” all contributed to the rise of Fascism in the early twentieth century.

Albright does deal with some of the issues of “societal ills” in a chapter in her book titled ‘ A Difficult Art’, She acknowledges that “of the people celebrating their sixteenth birthday this year, almost nine in ten will do so in a country with a below average standard of living”, that youth unemployment is high, wages are stagnant and have been so since the 1970s, technology is the major driver of job loss and the prevalence of social media means that it is harder for governments to get their message across. However, her prescription for people who demand more of their government is to call them “spoiled”, those who don’t vote are “lazy” and “we crave all the benefits of change without the costs. When we are disappointed, our response is to retreat into cynicism, then start thinking about whether there might be a quicker, easier, and less democratic way to satisfy our wants”. That she can see the ills but not hear the people gives us a clue as to why Donald Trump was elected, he had an ability to recognise discontent and he challenged the received wisdom and the institutions of the status quo.

Albright’s remedies for the above ills seem weak in the extreme, “address national needs together” and reclaim the “vital centre” do not deal with the urgent problems of electors and their frustration with their situation and what has gone before. A return to politics as usual as advocated by Albright will not work because the politics as usual have not solved the problems to which she refers.

What of Paxton’s “conservative complicities”? Neither Mussolini or Hitler seized power, they were invited to share power to subdue leftist populist movements. As Samantha Power states “it was the mob who flocked to fascism, but the elites who elevated it”. Paxton writes “At each fork in the road they choose the anti-socialist solution”. Fascism therefore was given legs by those who thought they could control the leader and the movement and who were scared by the rise of socialism. The rise of Progressive politicians in the United States and the conservative ‘establishment’ response will be a key guide to watch. As Power states “if it [Fascism] returns, [it] will do so not simply because of a rousing leader, but because of his timid accomplices”.

Albright begins her book with an epigraph from Primo Levi “Every age has its own Fascism”, she goes on at the end of the book to finish the quote “There are many ways of reaching this point, and not just through the terror of police intimidation, but by denying and distorting information, by undermining systems of justice, by paralyzing the education system, and by spreading in a myriad subtle ways nostalgia for a world where order reigned.” She uses the quote to warn of the dangers of Fascism, but the quote may equally apply to the politics of the last 40 years that led us to the election of Donald Trump and the elevation of strong men across the globe. Where a system of justice does not work for everyone, education is the preserve of the rich, elections are gerrymandered to the extent that it is pointless for people to vote, there is little, or no social safety net and politicians do not seem to listen or to care. The crisis in the liberal state is because of the public’s perception that politics and politicians are unwilling or unable to solve their problems or work for them. Albright offers no practical solutions to these problems or how we can construct something new from the old. Indeed, she prefers to look back at past presidents with nostalgia, failing to make causal links between their actions and the present situation.

Albright’s book finishes with a set of questions, the answers to which are supposed to warn us of leaders with Fascist tendencies. However, that which Madeleine Albright seeks to warn us of is already here, Donald Trump is President, authoritarians are being elected in increasing numbers around the world and with the imminence of Brexit, the European Union is set for an uncertain future. The question, which Albright fails to adequately answer, is what is the global community to do about it.

In the group Charlotte enjoyed the book but felt:

‘I didn’t seem to get from her quite enough explicit distinction making to help me become confident that I will know the next time I hear “fascist” thrown around in conversation whether the speaker is using the term in an informed way or just more emotionally and loosely.’

Stuart also enjoyed the book but also wanted a little more from it:

‘I would have liked for her to draw out her own theories of what social conditions she sees as most associated with the rise of fascistic tendencies, as well as, say, attributes of societies that successfully nip such tyrannies in the bud.’

Andrew agrees that:

‘Albright argues for a shift back to the centre. Let’s heed her advice’

Adam also enjoyed the book, particularly as:

‘it was grounded in history, which I loved, and it addressed specifically the many situations around the globe where fascists (whether they call themselves that or not) are in power, and how that impacts their people and the world.’

Due to an unexpectedly extended Christmas hiatus there was no book group dispatch last month. We concluded our reading of ‘The Perfect Weapon’ and began reading ‘Safe Passage: The Transition from British to American Hegemony’ by Kori Schake on 1st January.

February’s book was chosen during December and is ‘The Hell of Good Intentions: America’s Foreign Policy Elite and the Decline of US Primacy’ by Stephen M Walt, a nice follow on from Kori Schake’s book.

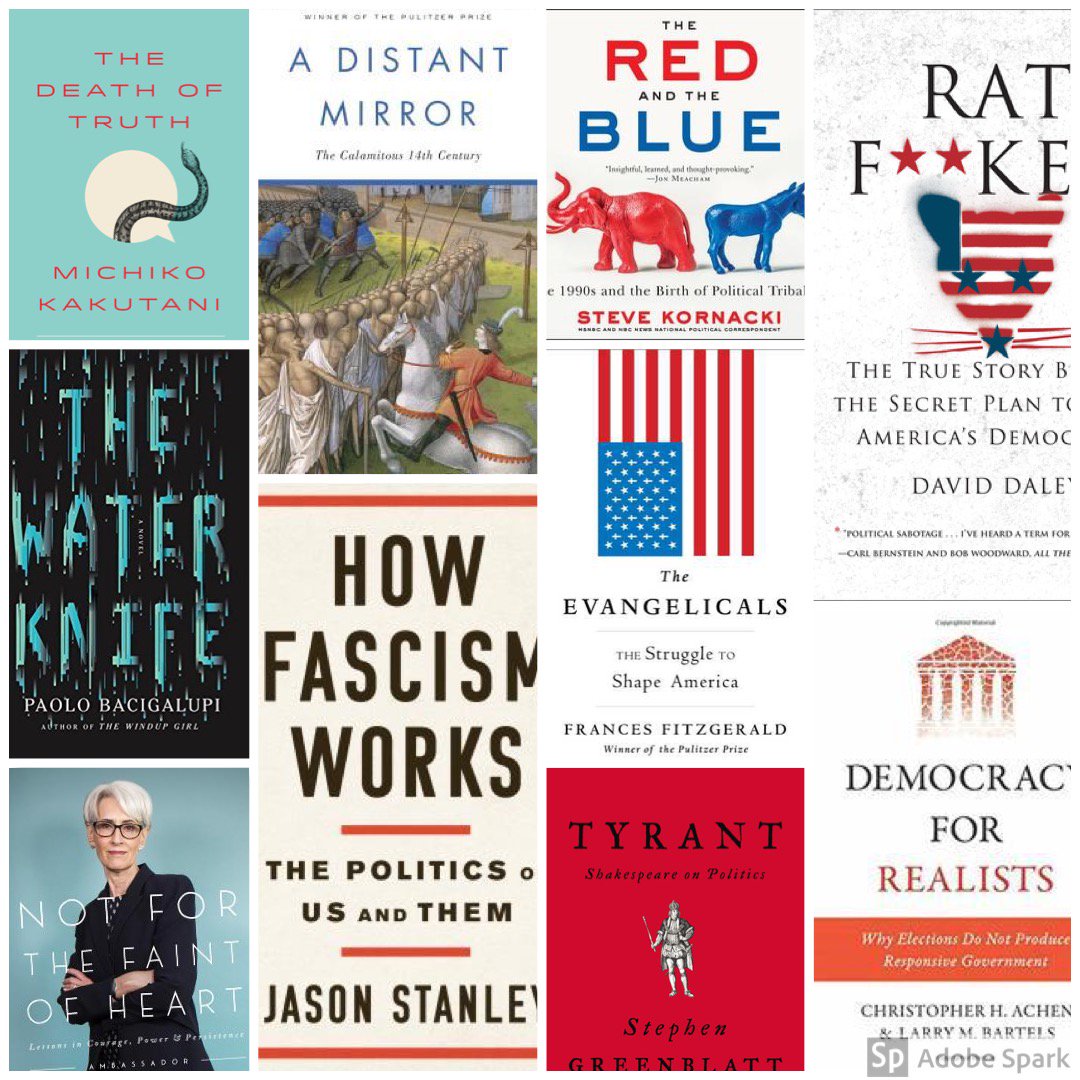

Our March book has just been chosen from a shortlist of 9 titles

Three books came through to the second round of voting:

“The Red and the Blue: The 1990s and the birth of Political Tribalism” By Steve Kornacki

“Tyrant: Shakespeare on Politics” By Stephen Greenblatt

“How Fascism Works: The Politics of Us and Them” By Jason Stanley

For the first time we had a tie in the results so ‘The Red and the Blue’ and’ How Fascism Works’ were subjected to a flash poll with March’s book being “How Fascism Works” by Jason Stanley.

Please note that as an Amazon Affiliate, we earn from qualifying purchases.