Kori Schake’s purpose in her book “Safe Passage: The Transition from British to American Hegemony” is to ensure we remember our past expressly in order that we can repeat it. Her subject is a state’s ability to set the rules of the international order and to enforce them, the hegemony of the title, and the conditions needed for a peaceful transition from one hegemon to another. In her opening paragraphs Schake proposes the transition from British to American hegemony as the only peaceful transfer of power out of the sixteen such transfers The Belfor Center’s Thucydides Trap Project identified. As such, the reasons for such a peaceful transition are important and worthy of study. Empires do not last forever and the decline and fall of the current hegemon is an inevitability.

Schake charts the transfer of hegemony between the upstart America and the British Empire over a period of approximately 120 years from 1821-1944. She chooses nine inflection points that demonstrate America’s growing confidence and the reaction of the prevailing hegemon to this challenge. She also looks at the effect of that change on the international community and seeks to apply the insights she has gained to potential challengers to American hegemony.

Beginning her examination with the Monroe Doctrine in 1923, Schake chooses a point in time which sees America under Monroe become ‘more fully belonging to the Americas’. Up to this point, the young America was facing inward, dealing with domestic concerns, its international policy limited to dealing with other powers preying on the fledgling country. However in declaring:

“The occasion has been judged proper for asserting, as a principle in which the rights and interests of the United States are involved, that the American continents, by the free and independent condition which they have assumed and maintain, are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European powers.”

Monroe clearly draws a line between the Americas and Europe, a change in policy that shows America defining itself not in terms of European power but as a new and “energetic future”. Schake posits this as a pivotal moment in which America “cast[s] it’s lot with other revolutionary regimes’. This is important both for America’s conception of itself and for the British conception of America. A continuing theme throughout the period Schake is studying is Britain’s view that the American political system, with its frequent elections, is inherently unstable and prone to chaos, whilst the American view of the European Monarchies is that they are undemocratic. However, perhaps for the first time, with Monroe’s Declaration, Britain sees the emerging America as a rising power. America also, Schake says, “would assert the universality of it’s values and advocate for the adoption of its domestic political arrangements”. A foretaste of the rules of the game America would adopt as a hegemon of the future.

The Oregon Boundary dispute and ‘Manifest Destiny’ some 12 years later not only proved a threat to Britain due to the land disputes but again, American’s conception of the British Empire and it’s system of governance as being inherently objectionable played its part in the crisis. Schake acknowledges that Britain “ had both force of law and force of arms to its advantage” and American belligerence cooled upon the “dispatch of thirty British warships to the Americas to cause a recalibration”. The eventual compromise however owed much to “the influence of public attitudes” in both countries. Schake points out that the danger from the emerging America was more to do with the appeal of it’s politics than it’s force of arms, an appeal the British were cognisant of and deeply wary of and which would continue to be a consideration in the years ahead.

The danger posed by the appeal of democracy and America’s political system is fully realised in British considerations over whether to recognise the Confederacy during the American Civil War. To acknowledge the legitimacy of the Confederacy would have implications for British rule over Scotland and Ireland due to swathes of immigration from those countries. America was in a unique position to exploit those familial links to cause internal strife. Also, by acknowledging the Confederacy and a “plantation protoaristocracy in the American South” would be to risk inflaming internal tensions over political representation in Britain. The British therefore held off from what would otherwise have be an advantageous move due to domestic political considerations. As Schake points out “America was unique as a foreign policy problem because choices about it could resonate back to Britain’s own politics.”

It is the Venezuelan debt crisis that Kori Schake pinpoints as the moment that the waxing and waning hegemons finally intersect, that “[America] realised and asserted its power” and the point when Britain had to reevaluate its relationship with the new hegemon. With the expansion of the Monroe Doctrine as a result of the crises, and America’s assumption of a “commitment to taking preventative military action on behalf of jilted creditors” ie European Countries, America had aligned itself with those “jilted” countries against American states and “had become a European power in foreign affairs”.

The Spanish American War, which took place between the two debt crises, illustrates how far the two countries, Britain and America, viewed themselves as aligned at this point. Formally neutral in the conflict Britain practiced a “benevolent neutrality” that in effect saw Britain acting in concert with America. Having won the war however America declared that temporary American control of Cuba would only be returned when they had a government and were able to discharge the duties of government. Having secured control of Cuba, Guam, Hawaii, the Philippines and Puerto Rico, America showed little appetite for releasing control of them – America had become an Empire.

With American expansion beyond its homeland borders and the expansion of democratic representation in Britain, Kori Schake believes the now two great powers recognised similarities in each other that they did not recognise in other great powers around them. It was this recognition and alignment that is unique among the hegemonic transfers. However, this alignment did not last long, with World War I America become “the banker and provisioner of European powers” whilst Britain emerged from the war not only in substantial debt to the United States but was experiencing domestic unrest and British business had lost out to American competition. Financial and economic superiority underpinned the ability of America to force compliance with its rules.

Following on from the Great War, the Washington Naval Treaties of 1922 see “Britain cede primacy to the United States” says Kori Schake. The United States was prepared to threaten Britain with an arms race that would bankrupt it if Britain did not agree to limit it’s naval armaments. As Schake points out “A risen America was prepared to impose its power on Great Britain to achieve the broader goal of shaping the international order”. The shaping of that international order included bringing Britain’s naval supremacy to an end. By the time of the treaties, Britain was just another state that America had to manage. Britain also had to look to other alliances to secure it’s imperial possessions. The alignment that had secured a peaceful transition from one hegemon to another was cracking.

Kori Schake’s final stopping point on her journey is World War II and the financial and military assistance given to the allies during the course of the war. The United States was by the end of the war the dominant Western power and in that position was interested in fostering new international rules. As such, America was prepared to assist in the recovery of vanquished states as long as they were prepared to follow the new rules of the game: “democratic governance, free markets, and adherence to what was coming to be considered the American order”.

One can not do justice to this examination of the transfer of power from one hegemon to another in this overview. “Safe Passage” is a book rich in detail and analysis with 87 pages of notes, further comment and discussion, and opportunities for further reading. Kori Scake’s final analysis make sobering reading in that the rising power of our time is China, the opportunity for alignment with which seems slim. If the successful transfer of power relies in part on a recognition of sameness, the current administration’s policy of power competition sees alignment as a dim hope.

In a further essay entitled “How International Hegemony Changes Hands” (Cato Unbound) Kori Schake expands on her theme of a rising China and the potential change in hegemony. She points out that the United States policy towards China has historically closely resembled that of Britain to the United States, “cajoling them into cooperation, but enforcing the rules of order it established until convinced that the United States would play by the established rules as a responsible stakeholder.” However, there are significant differences between the two situations, principally that the hegemon tends to want to recreate the international order in the image of it’s domestic order, and there is no evidence that smaller states find the Chinese domestic order attractive. Couple this with current US policy of power competition and the likelihood of a peaceful transition becomes unlikely, a prospect that should worry us all.

The bookgroup’s March book, which we have just started reading, is “How Fascism Works: The Politics of us and Them” by Jason Stanley the thread for which is available for comments.

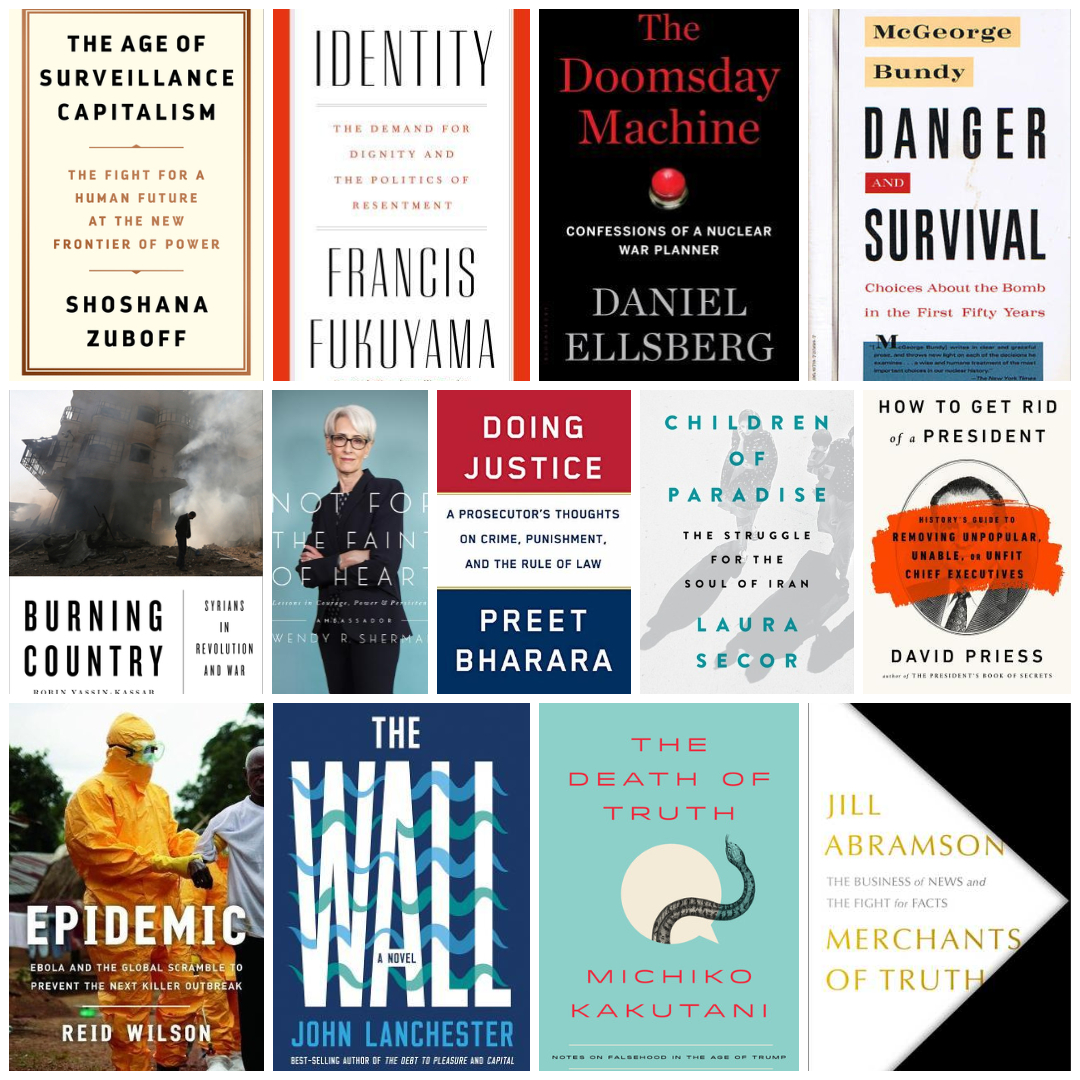

We have just picked our book for April from an initial field of 13.

Two books topped the initial poll:

Burning Country: Syrians in Revolution and War by Robin Yassin-Kassab & Leila Al-Shami

Doing Justice: A Prosecutor’s Thoughts on Crime, Punishment, and the Rule of Law by Preet Bharara

The book ultimately chosen for April is:

Doing Justice: A Prosecutor’s Thoughts on Crime, Punishment, and the Rule of Law by Preet Bharara

We also continue our read of The Hell of Good Intentions: America’s Foreign Policy Elite and the Decline of U.S. Primacy by Stephen M. Walt until the end of March.

We have introduced a Reading Partner folder. If you want to read and discuss a book (it does not necessarily have to have featured in a poll) put the call out for other like minded people who might want to read the book too and when you have at least one other person to read along, agree a time frame and start a thread. You can have just one person or as many as there are members in the group. The intention is to make the group more dynamic, our reading more diverse and involve more people in the group conversation.

Please note that as an Amazon Affiliate, we earn from qualifying purchases.